Today is the first Tuesday after the first Monday of November in a leap year, which means only one thing – it’s the 1463rd day of the US presidential campaign!

Election day, it’s nearly over. Like a sacred Leap Day, or a planetary alignment, this Tuesday is the only day in four years when nobody is running for president. For Hillary Rodham Clinton, said to have been running since at least the day she last left the White House, it is likely* to be the last day she is not President of the United States of America. In kind, in January 2017, Clinton is likely* to become the first woman president.

(*based on 538’s 69% chance of Hillary White House. no sure thing. UPDATE : 4:40am here, looks like Trump’s gonna win)

She would (figuratively) get the keys to her new presidential mansion – creatively named the “White House” after its fair complexion – sometime in the early hours of Wednesday morning, so long as at least 270 members of the electoral college pledge for her instead of her rival, Donald J. Trump.

This manner of selecting a Brand New Overlord dates back to the very first election, when 69 electors gathered in 1789 to pick the first president. Each elector was given two votes, on the understanding that all would give their first vote to George Washington, and the candidate who received a plurality of the second votes would win the prize of Vice President, which went to John Adams.

Of course, there was nothing democratic about this initial selection. Only the states that had ratified the constitution got to take part, with apologies to the indecisive North Carolina and Rhode Island. New York fell out with itself, so wasn’t allowed to play either. No matter, they’d have chosen Washington anyway. Only six of the ten participating states had a popular vote for their electors, of which only free people with sufficient property were eligible to vote.

College Dropouts

The Electoral College has managed to outlast many of these old ways, mainly because it has sanctified in Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution. Tomorrow, the US voters indirectly vote for Hill or Donny by voting for pledged electors, “stand-ins,” for their will. Each state gets as many electors as it has Senators and Houses Representatives, and DC gets three too under the terms of the 23rd Amendment. Each state is winner-take-all (except Maine and Nebraska, but let’s ignore them today).

In the old days, there was nothing holding these electors to the vote other than a Gentleman’s Agreement. Reneging was common; it happened in every election from 1796 to 1808, and frequently after that. Such characters were known as “faithless electors.” In 1820, one generous New Hampshire elector gave his vote to his pal John Quincy Adams. How kind – Adams wasn’t even running that year. It wasn’t always intentional. In 1864, Nevada only cast two of its three votes for Lincoln, because one poor soul, on his way to vote, got snowbound in Colorado.

In 1824 John Quincy Adams actually ran, and he set a few records along the way. It was the first election where they recorded the popular vote, and he won with 30.9% of it. That may seem low – because it is. He didn’t win the popular vote. Andrew Jackson got 40 000 more votes (41.4% of the total vote), and even got 15 more electors. However, Jackson didn’t take a majority of electors, and so the decision went to the House of Reps, or more accurately, a dusty, mysterious Washington office – these days the natural habitat of Cigarette Smoking Men leaning on a filing cabinet. There, Henry Clay gave his support (he’d won 37 electors) to Ol’ Quince, handing him the presidency.

Some say Clay did it for the position of Secretary of State, which he duly received. Others point out that Clay was politically closer to Adams, and he thought little of Jackson, proclaiming that “I cannot believe that killing 2,500 Englishmen at New Orleans qualifies for the various, difficult, and complicated duties of the Chief Magistracy” (wonder what he’d make of hosting the Apprentice).

Adams was the only person to win the president through the House, and as the first child of a former President to follow in his father’s footstep, he founded the first Presidential Dynasty, which have become increasingly popular in recent years (google Chelsea 2024, for further information).

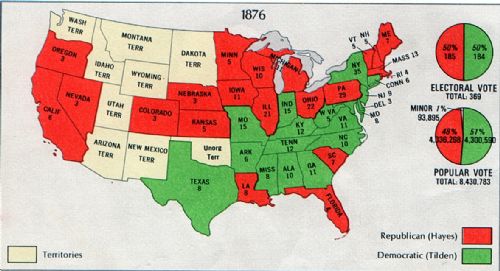

Adams, however, was not the last president to lose the popular vote but win the White House, thanks to the wonders of the Electoral College, a system whose beauty is supposedly in its simplicity but hides unending complications. It happened twice in the post-Civil War era, when there were a series of close elections – marked by mudslinging, shady deals and assassinations, as the USA struggled to reconcile its differences. It happened in 1876, when Rutherford Hayes won the college by a single elector (more of that an’ on). It happened again in 1888, where Grover Cleveland was temporarily evicted from the White House by Benjamin Harrison. Most recently, Al Gore won the popular vote by 500 000 in 2000, but George W. Bush took** Florida by 537 votes and with it came the White House.

(SIDEBAR – It seems a preposterous system in these incidences – but I’m not going to pretend I’m sat on some high British horse – the UK’s current government got a parliamentary majority of just 37% of votes cast, and 24% of those eligible to vote. The current Prime Minister was selected by a grand total of 199 people. That’s just the way of things.)

Elephants and Donkeys

The USA has a two-party system. The US has gone through a grand total of six party systems over the years, but the last few have all involved the Republicans and the Democrats. Both were originally founded for a purpose, but have shape-shifted a few times over the years, changing bases and constituencies in an eternal quest for power. The Federalists, Anti-Federalists, Whigs, Anti-Masons, Know Nothings, Bull Moosers, Progressives, Dixiecrats and Reformists have all come and gone, but the long-standing rivalry between the Reds and the Blues has stood firm.

The Democrats, symbolised by the donkey, sprouted from Thomas Jefferson’s now confusingly-sounding Democratic-Republican party. They initially saw themselves as the defenders of individual liberty against the malevolence of central power (embodied by Quince and Clay’s 1824 handshake), but as much as anything it became the very model of a modern political machine.

The Republicans (who claim the Elephant as mascot) were founded as an anti-slavery party in the 1850s, and quickly found support as the Whigs and Democrats pulled themselves apart in the slide towards civil war. Under William McKinley, the Republicans began their courting of Big Business, whilst the Democrats, retaining an element of southern populism, moved steadily towards social democracy characterised by FDR’s “New Deal.” Things changed again in the ‘60s, when the Democrats seceded the “Solid South” after their lukewarm embrace of the Civil Rights Movement. Meanwhile, Richard Nixon formed a “Southern Strategy” where the Republicans would say thinly-veiled racist, segregationist things to court the Deep South over to their side. Then Reagan came to town in the ‘80s and turned the entire USA over to neoliberalism (twas fertile ground, some might say), before Bill Clinton and the New Democrats responded by diluting the New Deal to incorporate the spirit of the Gipper.

So that’s how the parties came to look like how they look now. Sort of. They disagree on a fair few things, such as climate change, abortion, and the name of an east coast NFL team. But on many issues the two parties aren’t too far apart, such as taxes, foreign policy, business, trade, welfare, and the USA’s self-styled status as the “Leader of the Free World.” With the exception of Hillary and Barack, they’ve also tended towards wealthy, old white male candidates.

Their similarity is in part due to the centripetal nature of the Electoral College, and the parties’ longstanding record as efficient, election-winning political machines. It sits in striking contrast to a US society that is once again ripping itself apart; a fact that reflects itself in the electoral map. The USA is growing polarised on the fault lines of race, class, gender, policy and religion, and this is increasingly reflected in the voting habits in states. Swing states are becoming a rare breed. This phenomenon is not unique to the States; it’s happening here in Britain, starkly illustrated by the 52-48 Brexit vote. In the UK, our party system has splintered, but across the Atlantic the hegemony of the donkey and the elephant has held firm.

Sorry, Ross Perot.

Why? Well, US politics is a big money industry. It is difficult for a third-party campaign these days to compete with the big guns. Another reason is because of our good friend the Electoral College. As with much of the USA’s structure, it was designed to ensure that no one area could dominate affairs by racking up huge majorities in specific regions, whilst simultaneously ensuring the interests of regions and individual states are heard through its winner-take-all model. It’s nifty like that.

A successful third-party candidate has to compete across the country, and make sure they have a regional support base somewhere greater than that of the two main parties’ candidates. You need to be flush with cash to do that. Yet the USA has a lot of love for plucky outsiders. Perot did well in ’92, gaining 19.7m votes (19% of the total), but didn’t earn a single electoral vote.

In 2000, there was still a lot of frustration with the “lesser of two” choice that the main parties were now serving up. 2.8m voted for Green Party candidate Ralph Nader in an election where Bush and Gore were separated by just 500 000. In Florida, Bush was given the victory after weeks of recounting – lawyers everywhere – by just 537 votes. Nader had got 97,421 in the Retiree Alligator State. So many things can cause a 0.009% gap in an election. Weather, traffic, the 562 votes cast for the Socialist Workers Party, the “Butterfly Ballot” that supposedly encouraged votes for minor parties, hanging chads, votes denied to 1% of Floridians (and 3% of black voters) on account of being a “felon” including for crimes said to have been committed after the 7th November…buuuuuut for the most part Nader got the blame for taking Gore’s votes. It could be argued that the two-party system is so rigid in the States that Nader and his voters were naïve; myself, however, I’m uncomfortable with the notion that a candidate can take another’s votes, as if a candidate can own a vote before it is cast.

Third party candidates weren’t so popular after that. It’s easier these days to be an insurgent within one of the main political machines, thanks to their fluid ideologies and the Primary system of candidate selection, where anybody with enough cash or support can make an honest run at being a Democratic or Republican candidate for the presidency. It’s what Trump, Cruz and Sanders have tried this time around. Maybe we’ll see more of it in the future, especially on the red side. Once you’ve got the nomination, it seems the USA is so wrought in two that you’ve still got a chance at the White House. No matter how openly megalomaniacal you are, no matter how abusively racist and sexist you are in public and private, no matter how much of a nuclear-fallout-after-a-trainwreck-landslide-Godzilla-attack candidate you are, you’ll still likely do better than Dukakis. That’s just the way of things.

The Immortal Jim Crow

The voter suppression tactics that swirled around discussions of Florida 2000 were no stranger to presidential elections. They are no stranger still.

Back to 1876. Rutherford Hayes won by a single electoral vote, having lost the popular vote to Samuel Tilden. Tilden had taken 184 electors, but three Southern states, Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina, were yet to officially declare, amid reports of voter fraud and suppression that particularly targeted African-American voters. Importantly, these three states had Republican governors, and together their electors would see Hayes over the line. Here the Republicans set up “returning boards” to recount the election, root out Democratic voting fraud, and maybe doctor some results of their own.

By 1876 the Democratic voter suppression racket was fully operational. The party hacks made allegiances with Southern paramilitary groups the Red Shirts and the White (Man’s) League to intimidate black voters and break up Republican organisation in the South. It was working, and for the first time since the Civil War the Democrats look set to regain the region, sweeping even those districts with massive black majorities. Were there no vote-mangling at all, it is likely Hayes would have carried much of the South.

Unsurprisingly both sides claimed victory, each accusing the other of fraud. It got incredibly heated, and there were fears that a second civil war could erupt. Eventually, it (officially) went to Congress where a Commission voted 8-7 (along party lines) to give the states to Hayes. Secretly, however, in another smoke-filled room, Hayes met with senior Democrats promising a series of federal spending in the South and, importantly, the withdrawal of Federal troops from the region.

This ended Reconstruction, handing a monopoly of Southern violence to racist groups such as the Red Shirts, who would incorporate themselves into state militias. In exchange for a Republican presidency, the party seceded control of the South to their rivals, abandoning the newly enfranchised former slaves. Over the coming years, Democrats constructed a framework of laws alongside a widespread system of intimidation that locked out African-Americans from voting and running for office and denied them a whole host of civil liberties. This was the Jim Crow South, where black people lived segregated from white people in an Apartheid enshrined by the Supreme Court (Plessy v Ferguson, 1896). Although emancipated, ex-slaves in the South were not yet free.

Jim Crow was largely felled by the Civil Rights Movement, and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (on paper) ended disenfranchisement on the basis of race. Yet, as Florida 2000 shows, it still goes on. In 2016, it appears to be making a strident comeback, alongside the white nationalist fervour of the Trump campaign. Poor, minority areas across the USA generally have fewer voting stations, with less staff. Voting takes place on a Tuesday, and the polls close in the early evening. Those with long, unforgiving jobs may not be able to spare enough time in the day to queue to vote. Voting bans on felons – the USA is the incarceration capital of the planet – take millions off the register and disproportionately affect black people. In North Carolina, over 6000 voters, mostly black democrats, have been taken off the register in a process illegal under federal law. Jim Crow lives. It never really went away. That’s just the way of things.

Until Next Time…

Robert McCrum in the Guardian says that many believe the electoral system to be broken, “but it has seemed broken before and somehow staggers on.” Maybe. Maybe it’s worked fine for those it is made to serve. Maybe, like the Second Amendment, the Electoral College is so ingrained into the American fabric first wove by the Founding Fathers that to change it would be considered treasonous. Maybe, as when it was first created, the Electoral College keeps the lid on American tensions and papers over the cracks of this nation. Either way, it isn’t likely to change any time soon, but the way the USA has chosen its president over the last 200 years has had a great bearing on who ends up in the White House, affecting all of our lives from that oval office.

Soon we’ll know who that next person will be. In the meantime, relax. The next election begins in less than twenty-four hours.